left to right

Shroud #1 (2024) 30″ x 70″ monoprint, amaranth and pokeweed ink, watercolor, acrylic ink, paper, thread

Shroud #6 (2024) 22″ x 43″ monoprint, amaranth, pokeweed and indigo ink, watercolor, acrylic ink, thread

Shroud #5 (2024) 30” x 85″ amaranth and pokeweed ink, watercolor, acrylic ink, monoprints, thread

Shroud #4 (2024) 30” x 70″ monoprints, thread

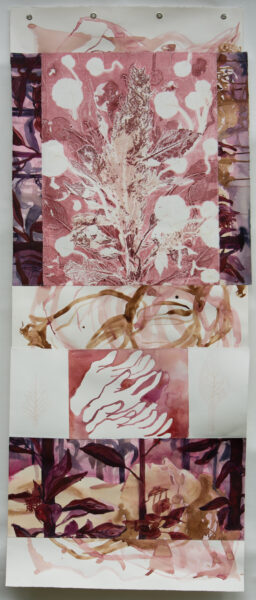

Shroud #1 (2024) 30″ x 70″ monoprint, amaranth and pokeweed ink, watercolor, acrylic ink, paper, thread

(detail on right)

Shroud #4 (2024) 70″ x 30” monoprints, thread

(detail on right)

Shroud #6 (2024) 22″ x 43″ monoprint, amaranth, pokeweed and indigo ink, watercolor, acrylic ink, thread

(detail on right)

Amaranth Shroud Installation at Traina Center for the Arts, Clark University, Worcester, MA, June 2024

Amaranth Shroud Installation at Gallery RAG, Gloucester, MA, July, 2024

Project Artist Statement

In the summer of 2023, I started drawing wrapped dead bodies in the news. The screen connects me to faraway places and faraway tragedies, but the images are right here, a part of my quotidian life, and I can recall them as if they were memories. Lined up on a beach in Libya, the sterile white bags held refugees who had drowned after their vessel capsized; bodies pulled out from the rubble of an earthquake in Morocco wrapped in colorful blood-stained blankets; and then later last year, and now—rows of shrouded Palestinians killed by Israel’s response to Hamas’ October 7th attack.

As I navigated this detached but real grief, I had an unlikely teacher – amaranth. I was first introduced to the red amaranth in my garden allotment in central Connecticut. One or two volunteers emerged between the landscaping fabric I used to impose control over the so called weeds. The land holds memory, stories, presence. What if we begin with a simple act—noticing what’s already here?

Though mostly considered a weed, an unwanted, a plant that doesn’t belong, amaranth’s leaves are edible, it is pest- and climate-resistant, and its seed is a superfood. It was first cultivated 6 – 8,000 years ago in Central and South America. The Aztecs incorporated its red juices into small figural sculptures for sacrificial ceremonies in honor of Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and sun. But when the Spanish conquistadors arrived, they outlawed the growing of amaranth because its uses and color were too similar to the blood of Christ in the Eucharist. It was competition for the Catholic church that aimed to convert the natives. Anyone caught growing amaranth could have had their hands cut off.

The amaranth in my garden has self-seeded again, the vibrant plants are poking up through the earth; this year there are hundreds and I am watching and listening and learning. Using ink I made from these beings, my figural drawings map dreamlike visions of my own death. “Bury me in the garden,” the drawings plead as they emerge on the page, the ink still changing—still alive.

“The land knows you, even when you are lost” says Robin Wall Kimmerer. This is what I yearned for, when, in the midst of my own grief related to the pandemic, I started this garden. I discovered connection and belonging, but the dueling reality of abundance and decomposition knocked me over. We have anesthetized and distanced ourselves from death, from discomfort, and this makes us fragile. Grief does not go away or get wrapped up in a pretty package and put aside; instead, it becomes a part of you, ready to re-emerge at any time. Like a seed, dormant.

The magic of seeds undergirds the resistance and rebirth of all life. Vivien Sansour, Founder of the Palestinian Heirloom Seed Project, spoke recently—in the midst of her people experiencing genocide—about the irony of how Palestinians preserve their seeds in ash. She says, “[The seeds] sit there in the ashes of things and their kin that have been burned to death, and they have to figure out a way to come back to life.”