Pockets Full of Walnuts

My toddler’s pockets are full of walnut shells. It’s a mast year, and the nuts litter her nursery school’s playground, and now, our house.

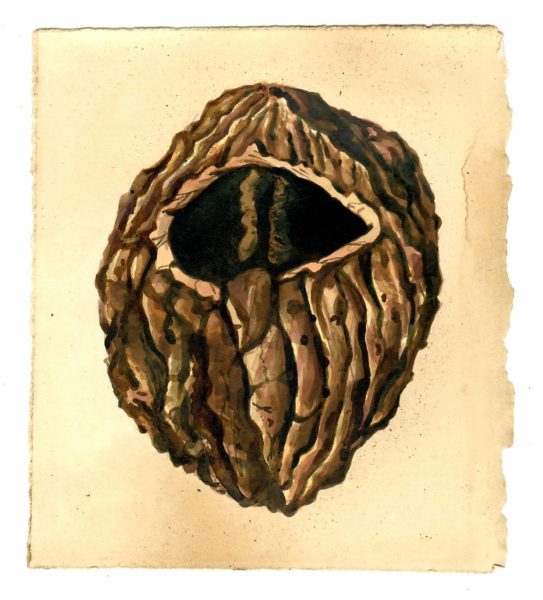

She has endless ways of playing with the shells: using them to bake “apple pie” in the living room cabinet where we keep the wifi box, lining them up to practice her counting, or gifting them to her loved ones. She rolls them over and between her fingers as she wanders from room to room. I find them everywhere. One morning my toes discover a forgotten shell on the bathroom floor and I pick it up, intending to discard it. But as I trace the texture with my thumb I pause and take a peek. Hard as stone, it is a miniature geological mountain range. In the dramatic shadows and sharp lines of the empty cavities, I see skulls. What are these things? I ask myself.

A mother’s love—her biggest hope. A coat of protection around her seed, these shells are failed attempts at offspring. I hold one of many hundreds of wishes dropped to the ground by the black walnut tree. I shine a light inside but cannot find a morsel of evidence of the nutrient—rich meat that would have held the embryo and fed the seedling. Humans use a strong metal lobster claw to crack into these – how on earth did the squirrels and chipmunks manage this feat?

In 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, we moved back to Connecticut. As I was researching the place through Wikipedia, my toddler was researching the land through her senses. How do we come to know something?

The Black Walnut (Juglans nigra), the only wild tree nut native to North America, can live to be over 300 years old. Humans have harvested all parts of the black walnuts for an abundance of uses—to eat, but also to drink, to cure, to clean, to write, to dye, to deter. For thousands of years our species have been entangled. Looking closely at the shells is my meditation, my way of being present with the natural world. Thích Nhất Hạnh, in his love letters to the earth, says, “We already are and we already have what we are looking for.” I let this wash over me while I draw, let it bury deep into my bones of understanding. But my mind wanders often, because drawing is thinking. Whose land are we on? Who has harvested this mother tree’s seeds in the past? How long ago? And her mother’s seeds? And her mother’s mother? Did my daughter’s ancestors walk under these branches? Did they fill their pockets with walnut shells?

(Left) Walnut I, 2023, walnut ink, flower extract, and acrylic ink on watercolor paper, 6.5″ x 6.5″”

(Right) Walnut II, 2023, walnut ink, red amaranth ink, and acrylic ink on watercolor paper, 5.5″ x 6.5″

(Left) Walnut IV, 2023, walnut ink, flower extract, and acrylic ink on watercolor paper, 6.75″ x 6.75″”

(Right) Walnut V, 2023, walnut ink, flower extract, and acrylic ink on watercolor paper, 5.5″ x 7″